Under its Mexican Presidency (2024-2026), the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has made it a priority to enhance risk-based implementation of its anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing (AML/CFT) standards as a vital means of enhancing global financial inclusion. Recognising how disproportionate anti-financial crime measures have yielded unintended consequences including the alienation of underserved communities from the formal financial system, in July 2025 the FATF issued new guidance to support public and private sectors in advancing financial inclusion. With accompanied complementary changes to the FATF Recommendations and Methodology, states now need to demonstrate concrete steps towards incorporating consideration for financial inclusion into their AML/CFT regimes, making what may have been thought of as a “nice to have” into a compulsory “need to have”.

What is Financial Inclusion?

The latest FATF guidance builds upon previous guidance from 2013, supplemented in 2017, including in how financial inclusion is conceptualised. The 2017 definition of financial inclusion emphasised providing access to “an adequate range of safe, convenient and affordable financial services to disadvantaged and other vulnerable groups”. The 2025 guidance goes beyond this understanding to emphasise usage as well as access, underscoring the reality that mere access to financial services without accompanying active uptake of those services and financial literacy does little to move the dial on serving the underserved. In this way, policymakers and financial institutions are given impetus to consider how the design of policy and financial products can not just improve access among the un- and underbanked, but how these can meet their distinct financial needs and correspond to their realities.

“Mere access to financial services without accompanying active uptake of those services and financial literacy does little to move the dial on serving the underserved.”

What Drives Financial Exclusion?

The FATF’s guidance suggests that the greatest impediments to financial inclusion stem from inadequate implementation (or perhaps understanding) of the risk-based approach (RBA), a cornerstone of the entire FATF approach to AML/CFT contained within FATF’s Recommendation 1. At its core, the RBA requires that all mitigating measures – whether they be national-level regulations, or the customer due diligence requirements of a financial institution – are proportionate to the degree of assessed risk, which is virtually always based on a risk assessment exercise.

Financial institutions are therefore called upon to embrace the inherent flexibility in the RBA to design AML/CFT controls that are proportionate to the degree of identified risk of money laundering or terrorism or proliferation financing, including simplified AML/CFT measures for lower risk scenarios and customers.

Financial exclusion tends to occur where over-earnest efforts to safeguard the integrity of the global financial system leads financial institutions to refuse, terminate or restrict banking services, like current accounts or loans, to individuals or groups to avoid financial crime risks instead of assessing and managing those risks. In other words, an overly cautious approach to implementing AML/CFT measures, one which is greater that the identified degree of risk and thus disproportionate, yields an unintended consequence of excluding legitimate customers from the formal financial system. The greatest burden of this effect typically falls on underserved communities in poor, rural or politically fragile contexts.

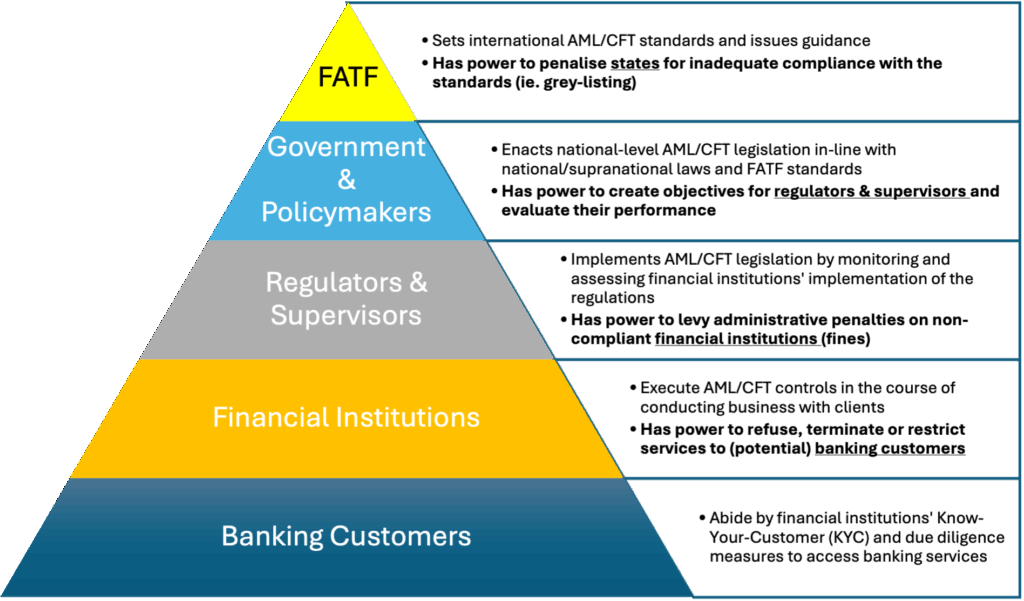

This behaviour on the part of financial institutions can be understood as a consequence of a hierarchical financial compliance structure (see Figure 1), whereby the threat of sanction from above for supposed AML/CFT deficiencies compels each level of the hierarchy to be overcautious and/or rigid in its financial crime risk tolerance, oftentimes leading to over-implementation or “gold-plating” of compliance measures.

The hierarchy of AML/CFT regulation and policy. Each level of this hierarchy receives instruction and faces scrutiny and possible sanction from their immediate superior (or, in the case of banking customers, face being de-banked or financially excluded).

Despite this hierarchy, the RBA as conceptualised by FATF infers the necessity of a “non-zero failure” approach to financial risk management (para 129), which recognises that, even after assessing risks and devising proportionate mitigating measures, some residual risk remains. Condoning some inevitable residual risk must therefore be enshrined at the top of the hierarchy and be allowed to cascade downward, with adequate assurances provided to each level that flexibility and bearing the acceptable level of residual risk required to financially include the underserved will not invite penalty.

The FATF’s new guidance seeks to achieve just this.

The Downward Cascade: Putting Guidance into Practice

Each stage of the hierarchy mentioned above is called upon by the FATF to adjust their practices to allow for this non-zero failure positioning, a necessary condition for enhancing financial inclusion.

Government and Policymakers

Starting with the governments and policymakers that implement FATF standards into national laws and measures, the FATF has made clear in changes to the Interpretive Note to Recommendation 1 (and mirrored in its updated Methodology) that states “should identify area(s) of lower risk to support financial institutions and DNFBPs [designated non-financial business and professions] to apply measures proportionate to those risks”. Revisions go on to stipulate that “where lower risks are identified, financial institutions and DNFBPs should be allowed and encouraged to take simplified measures to manage and mitigate those risks”. As such, in designing the AML/CFT legal framework within which supervisors and financial institutions and DNFBPs (together known as “obliged entities”) operate, policymakers must set a tone from the top in legislation that simplified measures are expressly permitted and desirable for lower-risk situations. Overly rigid legal frameworks breed timidity and engender a chilling effect that cascades down the above-mentioned hierarchy, serving to stifle efforts on the part of obliged entities to adjust their compliance measures to be proportionate with assessed risks.

Regulators and Supervisors

A major addition to the revised financial inclusion guidance is its much-expanded consideration of the role of financial regulators and supervisors in supporting inclusive financial systems. For these bodies, the RBA manifests in two domains: (i) given necessarily limited resources and time, supervisors must target their monitoring activities on where the greatest risk lie, while (ii) assessing the risk-based nature of obliged entities’ compliance measures, including their effectiveness and proportionality to identified financial crime risks.

Supervisors must also embrace and act in accordance with an uncomfortable but important truth: that risk assessment and the design of proportionate mitigating measures cannot eliminate all financial crimes risks – residual risk will remain and, occasionally, illicit activity will occur. In-line with that non-zero failure positioning, the FATF encourages regulators and supervisors to distinguish and specify between instances of isolated failures of good compliance systems among their supervisees (within which residual risk may show up – or a “good fail”) and systematically insufficient systems (a “bad fail”). Communicating this distinction to obliged entities themselves is needed to maintain a regulatory environment conducive to financial inclusion, including one which continues to encourage simplified measures for lower-risk scenarios and customers, even in the face of occasional “good fail” situations.

The guidance also underscores the importance of common risk understanding between supervisors and obliged entities, to forestall circumstances where, unsure whether their supervisor will concur than a scenario or customer is low risk, will hedge against being penalised by withholding simplified measures. Supervisors are also encouraged by the FATF to support obliged entities with determining acceptable forms of identification where customers lack certain forms of documentation such as national ID cards, and to articulate in precisely what circumstances simplified measures may be implemented. By offering these assurances, the supervisor establishes confidence among obliged entities that they may do their part to foster financial inclusion by extending simplified due diligence measures to lower-risk customers, free from fear of enforcement action or administrative penalties.

“… risk assessment and the design of proportionate mitigating measures cannot eliminate all financial crimes risks.”

Financial Institutions

Sitting at the bottom of the hierarchy and directly interfacing with the (potentially) financially excluded, financial institutions may be driven to “gold-plate” AML/CFT compliance owing to several concerns they face (para 104), all of which disincentivise them from adopting proportionate, simplified measures for low-risk scenarios or customers.

Banks may receive unbalanced messaging from supervisors or regulators that overemphasise the need for enhanced due diligence for higher-risk situations, and underemphasise the inverse (simplified due diligence for lower-risk situations). Further, shouldering residual risk is uncomfortable for firms given the reputational risks this poses, particularly concerning potential terrorism financing, which are beyond the powers of regulators to assuage. Maintaining correspondent banking relationships also pressures firms to adopt the possibly more conservative risk tolerances of international counterparts, who may be less willing to process transactions for customers that the respondent bank deems to be lower-risk, but which they (the corresponding bank) deems to be higher-risk.

Here, financial institutions’ provision of bank accounts or other financial service to underserved communities is contingent on successful implementation of the FATF guidance at all preceding levels of the hierarchy. Only then can obliged entities afford simplified measures and adapt customer identification and verification practices to meet the realities of underserved communities, many of whom lack commonly accepted forms of ID or transaction or credit histories in the regulated financial sector.

In many cases, a progressive or tiered approach to customer due diligence has allowed obliged entities to offer financial products like bank accounts with functionality that corresponds with the level of due diligence performed. Simply put, accounts with strict transaction limits or balance thresholds can be afforded to customers after only minimal identification and verification, with higher limits and functionalities offered if/when the customer can provide additional information. Recalling the FATF’s enhanced definition of financial inclusion, however, even basic accounts would need to be commensurate with the financial needs of customers to yield positive financial inclusion outcomes (ie. if balance thresholds are so low as for the account to be of no use to the customer, who must instead compensate with informal systems to meet their needs, the customer has not been genuinely incorporated into the formal financial system).

Conclusion

Apart from concrete revisions to the FATF Standards and its Methodology that are intended to further embolden the RBA and advance financial inclusion, states should also take from the FATF’s latest guidance an appreciation that financial exclusion is a risk to financial integrity in its own right.

When alienated from the formal financial system, underserved persons must rely on informal and unregulated alternatives to meet their needs, generating an overreliance on cash and driving informal economic systems lacking in transparency and which are conducive to money-laundering, terrorism financing and other threats to the integrity of the financial system. This conceptualisation brought by the FATF ought to shift perceptions away from financial inclusion being seen as a separate aim of economic development practices, and towards embracing a view of complementarity between financial inclusion and the overall fight against illicit finance.